Margret Hamilton

Pioneering Engineer, Motivating Leader & Working Mother

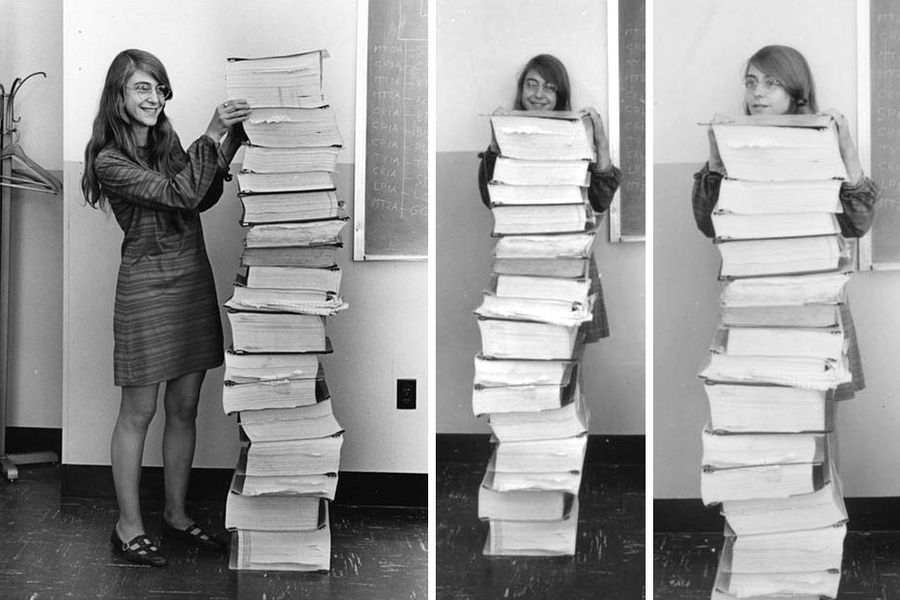

Margret Hamilton stands infront of some copies of code written for the Apollo Guidance System by her and her team.

Credits - MIT Museum

A Pioneering Engineer

Margret led the Software Engineering Division of the MIT Intrumentation Lab. Her team had only one task: Write the code that sends humanity to the Moon. This seemingly impossible task was made possible on July 20th 1969 when a 3 man crew used her team’s program and landed successfully on the Moon. This feat had many challenges all along the way but the agility and resilience of Margret and her team proved that no challenge was impossible for them.

Many of the practices established today in the field of Computer Science and Engineering build on the foundations that were laid by Margret Hamilton. She is also the first person to coin the term “Software Engineer” for a person designing and developing code.

Margret and her team developed the program for the Apollo Guidance System (AGS) with brilliant error-checking and error-handling functionality. This allowed the astronauts to focus on the mission rather than just trying to troubleshoot the error messages all the time. This laid the grounds-word of what every software program does today that can detect user errors and are programed to accomodate for user errors and other technical issues.

A Motivating Leader

The thing that influences me the most about Margret Hamilton is that she was tasked with leading a team of engineers to do something that was never done before. The task becomes even more difficult when software development was not something that was considered a key department or industry. Very quickly the NASA and MIT personelle working on the Apollo project realized the importance of software and Margret’s team rose to the occasion to provide the mission with it’s critical guidance systems.

I really like this quote from Margret Hamilton about the Apollo program:

From my own perspective, the software experience itself (designing it, developing it, evolving it, watching it perform and learning from it for future systems) was at least as exciting as the events surrounding the mission. … There was no second chance. We knew that. We took our work seriously, many of us beginning this journey while still in our 20s. Coming up with solutions and new ideas was an adventure. Dedication and commitment were a given. Mutual respect was across the board. Because software was a mystery, a black box, upper management gave us total freedom and trust. We had to find a way and we did. Looking back, we were the luckiest people in the world; there was no choice but to be pioneers.I was really motivated by the morale of Margret’s team and their commitment to deliver for team success. This also influenced my take of management because software was a ‘black box’ to them, they trusted the engineers who had the capability to figure out the solutions to the problems. Had they been micro-managing the team, the results of the project would have been very different.

A Working Mother

While working on an impossible feat of engineering, Margret could not leave her other responsibilities behind. So, with amazing dedication to her career and team, she also had equal dedication to her family and most of all her daughter, Lauren. In fact, Lauren shared many hours in the MIT Instrumentation Lab while her mother worked. Lauren even figured out an edge case where the Apollo computers would malfunction. I think it is very important for an individual to manage their family life and career. I have tried to follow Margret Hamilton’s example to create a balance with my work responsibilities and my personal life.